To really understand the background of Danuta Czech’s Auschwitz Chronicle, we need to understand the dynamics of the German-Polish relationship during the past 200 years or so. Or rather, we need to understand that dynamic for the past 1,500 years, so let me take you back in time. Actually, far back in time.

Modern gene-sequencing technique has discovered recently that around 5000 B.C., a major invasion of Europe happened coming from Asia. It brought with it a strain of the plague which was heretofore unknown to Europe. Having no immune defense against that disease, most of the then-indigenous populations of large swaths of Europe seem to have been wiped out and replaced by the Asian conquerors. Hence, what we today call “Europeans” are instead for the most part descendants of these Asian invaders. I mention this to make it clear that Europe has never been the eternal home of this or that ethnic group of peoples.

Strictly speaking, one could go even farther back in time and insist that Europe was first populated by Neandertals, which were subsequently replaced by Modern Humans (I refuse to call them Homo Sapiens, because there is little wisdom in our race…), while both groups were interbreeding to some degree. We know this, because, again, modern gene-sequencing technologies have made us understand what sets Neandertal DNA apart from Modern-Human DNA, and we see sequences of Neandertal DNA embedded in the DNA of modern Europeans (and Asians). Whatever the dynamics were that replaced most Neandertals with Modern Humans – diseases, war, higher reproductive success – the fact remains that the original human inhabitants of Europe – Neandertals – were replaced with Modern Humans.

This goes to say that complete population replacements are a regular occurrence in the history of mankind in general, and Europe in particular. The term “indigenous” is therefore relative. Apart from certain areas of Africa where evidently humans evolved, humans are actually an invasive species everywhere else, not “indigenous.” Seen from that perspective, the replacement of America’s first set of “indigenous” people by European invaders by means of diseases, war and higher reproductive success starting in the 17th Century is just one more chapter in the long sequence of similar events in human history.

The modern history of the area which today we call Poland and Germany is no exception to that rule. Not being marked by any kind of natural borders, ethnic, political and cultural “borders” have always been shifting forth and back in that region.

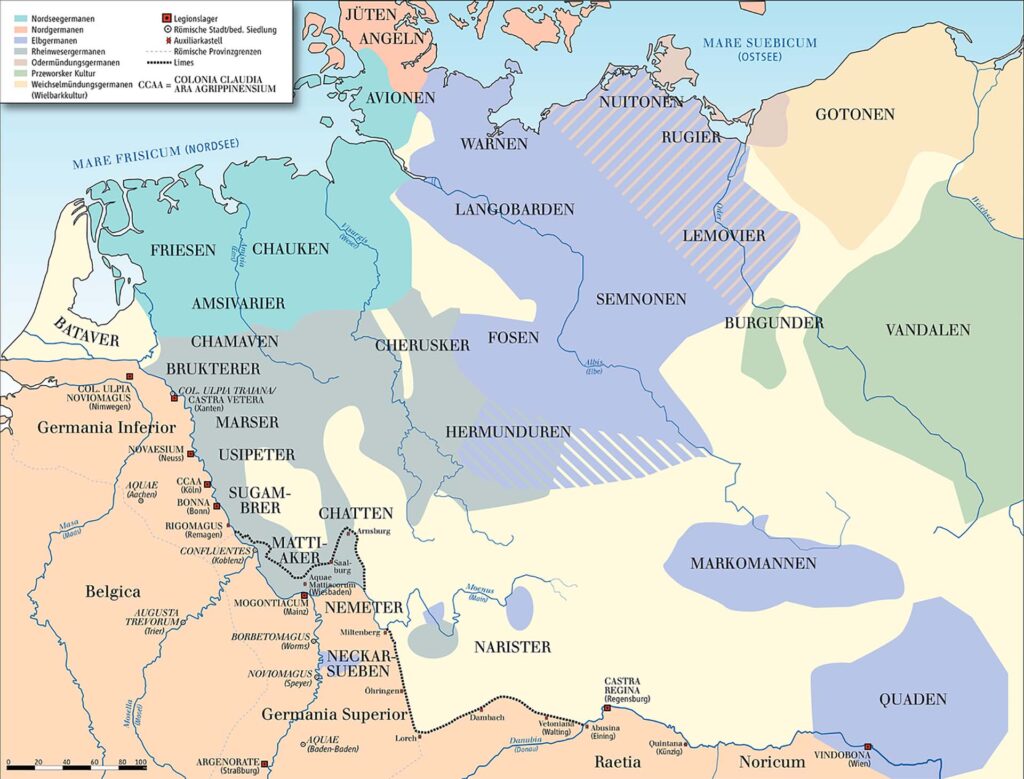

Illustration 1: Map of Central Europe around 50 A.C., showing the rough settlement areas of several Germanic tribes.

In recorded history, the first noteworthy event was the so-called Migration Period that started sometime during the 4th Century A.C. and lasted well into the 6th Century, triggered to some degree by pressure exerted by Huns invading Europe from the east, but also by the deteriorating Roman Empire that started making alliances with Germanic warlords in an attempt to stabilize the western part of the Empire. Without going into details, it is safe to say that earlier assumptions of a “peoples’ migration,” where entire Germanic tribes set out to migrate west and south, bringing about the collapse of the Roman Empire, are no longer considered to be true. It is far more likely that the Germanic tribes stayed for the most part where they were; that some groups decided to emigrate to the greener pastures of the Roman Empire, and that some Germanic warlords took advantage of Roman weakness to wage war against Rome, or to form alliances with Rome in order to gain control and power with Rome’s consent. Either way, most of the members of the Germanic peoples living in Central Europe were still there when this migration period ended.

The map on the previous page shows the settlement areas of several Germanic tribes around 50 A.C. We see that the Vandals used to reside in what is today’s central Poland, whereas the Gotones are thought to have settled in the area later called Eastern Pomerania, West and East Prussia. Central Germany – today’s Western Pomerania, Mecklenburg, Brandenburg, Saxony and Thuringia – was the home of a number of related Germanic tribes.

After the collapse of the Roman Empire and the end of the Migration Period, we enter a few centuries without much of any written record as to what was going on in Central Europe. By the time Charlemagne conquered parts of what is today’s western Germany (mainly Saxony), the map had changed. When Charlemagne’s short-lived Frankish Empire disintegrated, the precursors of today’s Germany and France emerged, with Germany being limited to an area which coincides roughly with what was to become Austria and West Germany after World War II. The peoples living in what is today’s East Germany and Poland were to a large degree linguistically no longer Germanic, but Slavic, although they were not organized in any way as independent political units, if at all. In the ensuing century or two, the territories between the Rivers Elbe and Oder, which were already tributary territories during the Frankish Empire, were subsequently incorporated into what was the precursor of Germany. Poland entered the political scene in the late 10th century, and this is where the history of German-Polish relationships starts. I will not discuss here any of the many petty conflicts between the various dukes, kings and emperors of both nations, as they had little impact on the people. Let me explain why.

During those ages, political rule had little if anything to do with ethnic commonalities. To put it simply, rulers expected their subjects to pay taxes and to serve in an army, if requested, but no one ever interfered with what languages people spoke or what cultural traditions they followed. Religious associations were important – people were converted to Christianity with fire and sword if needed – but since there was neither any centralized educational system in place nor any kind of structured public administration, language simply didn’t play any role. The Church spoke Latin for many centuries to come, and any kind of official government business was also conducted in that old Lingua Franca in most European countries. Hence, whether a person spoke Sorbian (a western Slavic language) or Saxon (a northern German dialect) made no difference to any official. The idea of nationality, ethnicity and language became important to European rulers only during and after the Napoleonic Wars, when the European nobility needed to obtain popular mass support for their wars against unified and nationalized France.

Now back to the Polish-German nexus. Two decisions of members of the Polish nobility had a major impact on that relationship. The first was the decision of the Polish Piast Dynasty in Silesia toward the late 12th Century and throughout the 13th Century to invite settlers to their region, which consisted to a large degree of uninhabited, forested lands. Many German settlers followed this call, many of them from Frankonia (today’s northern Bavaria); among them also my paternal ancestors (to this day, the last name Rudolf (with an F) is most-common exactly in Frankonia). They settled in an area whose major town is named after the settlers: Frankenstein (yes, the infamous one, but it has no castle). Within two centuries, the population of Silesia grew by a factor of ten, partially by immigration, partially by the economic and thus also reproductive success of the new settlers. By the 14th Century, Silesia was dominated by the new settlers. It was turned from a thinly populated Polish area to a densely populated German area. That development was sealed with the 1335 Treaty of Trentschin, with which the Holy Roman Emperor (who was elected from among and by the German kings) waived all claims to Polish territory, while the Polish king waived all claims to Silesia “for eternity.” Subsequently, major parts of the border between German Silesia and Poland were among the most-stable borders in Europe for many centuries.

Illustration 2: Settlement areas of various Prussian tribes in the 13th Century in what was later to become West and East Prussia.

The second decision was made in 1226 by Piast Duke Konrad I of Masovia, when he asked the Teutonic Order for help in his attempt to conquer the pagan, Baltic-speaking Prussian tribes living in what was later to become West- and East Prussia (see Illustration 2). They had resisted Christianization and conquest by the Polish Duke for many years. The Teutonic Order, which had been formed to conduct the infamous Crusades to the “Holy Land,” was already in control of the regions just west of the Prussians’ territory. The knights made short work of the Prussians, conquering and christening them in quick succession with fire and sword, later expanding that outreach all the way up to the Gulf of Finland, hence conquering what was later to become Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia in the process.

The dominance of the Teutonic Knights in this part of Europe came to an end after they lost a major battle against a combined Polish-Lithuanian army in 1410, and then again some 40 years later, after which the Teutonic Order could maintain control only over East Prussia, except for a sliver of land in the midst of it that was controlled by Poland (the Ermland). At that point in time, the Holy Roman Empire’s (that is to say: mostly German) control over most of Europe was dwindling, whereas Poland rose to a major power in Europe. This era came to an end in the late 18th Century, however, when a lack of firm leadership made the Polish state a victim of its neighbors, who carved it up in the so-called Partitions of Poland between 1772 and 1795.

Again, I must emphasize that none of these aristocratic, military or nobility reigns over a certain region or people had much of an influence on how the people organized their lives, what cultural traditions they followed, and which languages they spoke. Shifts in what languages people spoke were mainly driven by reproductive success and by economic developments. If you lived in a region where being able to speak German, Polish or Lithuanian was advantageous for economic success, then that’s what people did.

All this changed when Napoleon’s armies swept through Europe. Napoleon reestablished a Polish state after he defeated the Prussian army and invaded Russia, but that was not to last. With Napoleon’s retreat from Russia and Germany, all Polish territories briefly assigned to a Polish state were once more gobbled up by Prussia, Russia and Austria. This time, however, nationalism had been awoken among Europe’s nobility, among the political, financial, economic and intellectual elites as well as to one degree or another among the common people. Both the administrations in Prussia and Russia introduced policies in their territories mainly inhabited by Poles exerting pressure to become good German or Russian citizens, respectively. When Germany got united in 1871, triggering a wave of German nationalism, Germany’s policy toward its Polish minority radicalized: All schools in Germany had to teach all topics in German (except religion), schools in areas with a Polish majority included. German became mandatory for all matters of state in the judicial, legislative and executive branches. Though this pressure to use German as the language never reached any level that could be called persecution, the Polish minority was not pleased, to put it mildly. This “gentle” way of forcing the assimilation of a minority is quite common among nations occupying minority areas. France has been doing this in Alsace, and Italy in Southern Tyrol, for instance. To cut this long story short: self-determination was denied the Polish minority, and that was going to backfire on the Germans later.

A little over 100 years later, at the end of World War I, things were going to be put to the test. Although Germany had created a Polish state, a “monarchy,” already during the war, giving it the ethnically Polish territories once occupied by Russia but not an inch of the ethnically Polish territories occupied by herself, this construct was just as short-lived as Napoleon’s creation had been.

In late 1918, Germany accepted the armistice conditions as suggested in Woodrow Wilson’s 14-Points Program, which, among other things, promised self-determination for the peoples of Europe – or rather only to those that were controlled by the Central Powers. Had these conditions been kept, Germany had little to fear. But such was not meant to be. As soon as Germany and her allies laid down their weapons, the other belligerent powers were supposed to do the same, but instead they used their weapons to force a peace onto the Central Powers that had little to do with self-determination. Instead, they started carving up the Central Powers’ territories without ever asking most of the populations involved whether they agreed with it. Alsace-Lorraine was given to France – without any plebiscite (and with the subsequent expulsion of some 100,000 Germans who had migrated to that area since 1871). The Eupen-Malmedy area was given to Belgium – without any plebiscite. Southern Tyrol was given to Italy – without any plebiscite (and facing Mussolini’s aggressive assimilation policies, some 75,000 Germans left the area by 1943). Southern Carinthia was given to a never-before-seen, unstable country named Yugoslavia – without any plebiscite. The city of Ödenburg was given to Hungary – without any plebiscite. The entire area of Bohemia, Moravia and Slovakia was integrated into a never-before-seen, unstable country named Czechoslovakia – without any plebiscite (resulting in the later Sudetenland Crisis and the ultimate disintegration of that state). Most of West Prussia and the Posen/Poznan Province were given to Poland – without any plebiscite (a plebiscite in the Posen/Poznan area might have been the only one which the Germans might have lost).

The only areas that did see plebiscites were: a) the border area between Denmark and Germany – and its fair result was honored by all sides; and b) some areas claimed by the new Polish Republic: a few eastern counties of West Prussia, southern East Prussia, and Upper Silesia. But here, things didn’t develop as anticipated. In particular in Upper Silesia, things got out of control. In fact, as soon as Germany laid down her arms at the end of World War I, Polish paramilitary units picked up their weapons in an attempt to conquer the Posen Region as well as Upper Silesia, a much-coveted war booty due to its rich coal mines and metallurgic industries. The new Polish government was hell-bent on getting their hands on this area, and it did everything to bully the local population into voting for Poland in the upcoming plebiscite, which was held only in March 1921, hence more than two years after the end of the war. This campaign to gain control included armed “uprisings” of Polish paramilitary units led by Wojciech Korfanty and supplied with weapons by the Polish government, meaning that the Polish side tried to force a separation of these areas from Germany by waging an outright war on the local population, resulting in something very close to an undeclared war between the two nations’ paramilitary forces. When the plebiscite was won by Germany in Upper Silesia (only a few counties in the very southeast had Polish majorities) and the Poles feared never gaining control of areas they wanted, they staged another “uprising.” In the end, to assuage the Poles, the areas with the most important coal mines were ceded to Poland, although even some of them had voted for Germany.

Illustration 3: Had the inhabitants of the areas subjected to a plebiscite voted according to their declared primary language, Poland would have obtained parts of southern East Prussia.

The situation in East and West Prussia was not quite as heated, since the greater part of West Prussia was never to see any plebiscite, because Poland claimed that this area was mainly inhabited by Poles, and because Wilson’s 14 Points had promised Poland access to the Baltic Sea, which allegedly required the formation of a corridor through German territory, no matter what the local population thought about it. Furthermore, Poland had hoped that the population in the areas of West Prussia and southern East Prussia (Masuria) would vote for Poland, as it was inhabited to a considerable degree by people whose primary language was Polish according to a 1910 German census (see illustration).

When the actual votes came in after the July 1920 plebiscite, however, even the Germans were stunned. For instance, the inhabitants of the County of Ortelsburg in southern East Prussia, some 70% of whom had declared Polish as their primary language only ten years earlier, voted 99% for Germany. The situation was similar in West Prussia. Here, the County of Marienwerder, the west-most county to ever see a plebiscite which had a self-declared Polish-speaking minority of some 10%, saw 93.5% of all voters cast their vote for Germany.

Illustration 4: The actual results of the plebiscite indicate that the vast majority of native Polish speakers still preferred living in Germany rather than seeing their home region transferred to Poland.

An exception from this ongoing tussle between Germany and Poland over these territories was the City of Danzig, which was to serve as Poland’s access port to the Baltic Sea. This city, which had been dominated by Germans for centuries – no matter who the ruling power was – had a minority of only some 2% of native Polish speakers in 1910. Had a vote been cast there, it could easily have resulted in 99.9% votes for Germany. Under these circumstances, the League of Nations decided to separate the city with generous surrounding areas from Germany, yet instead of giving it to Poland, it was put under the administration of the League of Nations, which never had any real power to begin with. This impossible situation was to become the focal point around which World War II would ignite twenty years later.

The second Polish Republic of the inter-war years was a dictatorship that was never seriously interested in having any plebiscites. It acquiesced to the Western Powers’ decision in this regard only disgruntledly. Where these constraints of international power politics were missing, they showed their real faces: concurrent with the plebiscites on its western borders, Poland started a massive war of conquest on its eastern border by invading the fledgling Soviet Union, then still embroiled in a massive civil war. Poland “got lucky,” because the Soviet Union was weak at the time, so in the end, large swaths of Belorussian and Ukrainian territories, inhabited only by a usually weak Polish minority, were taken from the Soviet Union, and integrated into inter-war Poland – without ever having any plebiscites there. Needless to say, the Poles didn’t make friends in Moscow with this move, which later came back to bite them when Stalin and Hitler agreed to partition Poland once more in 1939.

As soon as its borders were notionally consolidated, Poland went on a mission to turn its new territory into an ethnically monolithic country. Any Lithuanian, Belorussian, German, Jew or Ukrainian disagreeing with assimilating and being a good Catholic Pole felt the pressure rising. The declared aim was to drive out anyone who did not want to assimilate. The ultimate goal was to undermine any potential future claim of any neighboring country for a border revision, which could be bolstered by the fact that foreign nationals were living in areas formerly controlled by that country. The situation was therefore particularly serious for Germans residing in once-German regions, particularly in West Prussia. Legal as well as extra-legal measures by Polish society to alienate them to the point where the only reasonable option was emigration to Germany were increasing. Already in 1921, there were a few riots against Germans, and by the end of that year, almost 50% of the German-speaking residents in Poland had left the country and moved to Germany. As US-American historian Richard Blanke put it (pp. 64f.):

“In many respects, Poland’s treatment of its German minority [initially] resembled Prussian Polish policy before 1918: harassment of political organizations and the minority press, undermining of minority schools, attacks on the minority’s land property, and economic discrimination by the state.”

In the meantime, Polish foreign policy tried numerous times unsuccessfully to persuade France to join them in a “preventive” war against Germany, trying to obtain even more territories from its neighbor up to the Rivers Oder and Neisse. Poland’s threatening stance increased when Poland’s leader Marshal Józef Piłsudski died in 1935 and was replaced by more-aggressive politicians. The culmination point was reached after Great Britain gave its infamous blank check to Poland in late March 1939, promising to fight alongside Poland in “any action which clearly threatened Polish independence,” even if that was a Polish aggression against Germany leading to a conflict between the two nations. The Polish media subsequently stirred up an anti-German hysteria in Poland which led to an escalation of assaults against ethnic Germans and their institutions, leading to a mass exodus of many of the remaining Germans from Poland in the summer of 1939. Talk about a swift war against Germany, accompanied by threats against the German minority in Poland, was rampant in the Polish media. All attempts by Germany to negotiate fell on deaf Polish ears. When war finally broke out, German units advancing into Poland discovered many cases where members of the German minority had been murdered by Polish mobs during what can only be described as a country-wide pogrom. The most prominent of them was the so-called Bromberg Bloody Sunday.

What I have reported so far is information that can be found in standard sources accessible to all. Even a search of Wikipedia will confirm the things I have written here. They are not contentious. When it comes to events during the German occupation of Poland, opinions diverge, however. An uncontested fact is that National-Socialist Germany did not care about plebiscites either if they could get around them by way of force. They displayed that attitude clearly when occupying Czechia in early 1939, and they showed it again in Poland. While Hitler’s Germany made multiple suggestions to have plebiscites in the Corridor during peacetime, once the Germans ruled the area starting in September 1939, they never bothered asking anyone whether their rule there was welcome. In addition, Germany annexed areas south of East Prussia that had never been inhabited by any significant number of ethnic Germans. Next, the policies implemented in the “recovered” territories and the newly conquered ones were designed to reverse and supersede the results of the Polish inter-war policy of ethnic pressure aiming at clearing the area of Germans. This time, Poles were resettled out of these areas, and Germans who had once resided there, plus new ones, where settled in it again. This much is uncontested.

What is contested is the number of Polish civilians who perished during the war. Mainstream sources parrot the Polish claim that Six Million Died. Yes, you read that right. The claimed victim number is the same as that claimed for Jewish victims of National-Socialist Germany, its foundation is just as shaky, and its use to justify claims against Germany and to instill an eternal feeling of guilt and repentance in Germans is exactly the same as well. Here, Polish and Jewish interests and agendas in historiography coincide.

There are two problems with the death toll. The first is that half of this death toll is said to have been Jews living in Poland. I will not discuss the shaky foundation of that claim here. The other half is based on the claim that Poland in its present-day borders lost three million people compared to the population that lived there before the war. The problem is that large swaths of what is today’s Poland weren’t Polish and weren’t settled by Poles up to the end of the war. These were German provinces settled almost exclusively by Germans who fled or were expelled from these lands at war’s end or shortly thereafter (East Prussia, East Pomerania and Silesia), many of them dying in the process. These aren’t Polish victims of war, but German victims of Polish ethnic cleansing (see O. Müller 2003 for details).

Which brings us to the immediate post-WWII era. During the Potsdam Conference in the summer of 1945, the Allied victors hammered out a basic agreement on what to do with Germany. First, Germany was defined as being the country in the borders of 31 December 1937, hence before the territorial gains that it won after this date (Austria, Sudetenland, Memel Region). Then, in Section XII. of the Conference Agreement about “Orderly Transfer of German Populations,” we read:

“The Three Governments, having considered the question in all its aspects, recognize that the transfer to Germany of German populations, or elements thereof, remaining in Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary, will have to be undertaken. They agree that any transfers that take place should be effected in an orderly and humane manner.”

Keep in mind that the German populations “remaining in Poland” had to be transferred, that Germany had been defined in the borders of 31. December 1937, and that the areas of that very Germany east of the so-called Oder-Neisse-Line were put only “under the administration of the Polish State” (Point VIII.B. of the Agreement), but “ending the final determination of Poland’s western frontier” were not a part of Poland proper – yet. Hence, strictly speaking, if taken literally, this agreement did NOT imply that the German population living within Germany of 1937 but east of the Oder-Neisse Line was to be expelled. But that is exactly what subsequently was done. My father and his family were expelled from their century-old home in Frankenstein County in 1946, together with millions of other Germans in Silesia – remember the Treaty of Trentschin: Poland waived all claims to Silesia “for eternity” – Eastern Pomerania, West and East Prussia (although the vast majority of Germans had already been evacuated from East Prussia at war’s end).

Compared to the bestial mass slaughter that broke out against ethnic Germans in Czechia and in Slovenia at war’s end, costing the lives of hundreds of thousands of Germans, the ethnic cleansing taking place in the eastern German provinces was relatively “humane” – if any ethnic cleansing can ever be humane, and considering the fact that millions were expelled with not much more than what they could carry, to more-westerly regions of Germany that were devastated, in utter ruins, starving and stricken with epidemics. Many died of exhaustion and hunger simply because under the prevailing circumstances a safe journey was impossible.

Those Germans who decided to stay behind – or the roughly one million Germans of the Upper Silesian Industrial Area who were kept behind because their expertise in running the factories was needed by Poland – had to assimilate quickly or experience harsh treatment by their new Polish masters. In fact, camps formerly established by the National Socialists to incarcerate criminals, dissidents, persecuted minorities and PoWs, were taken over by the new Polish masters and used to incarcerate Germans unwilling to bend to the will of their new masters. John Sack has aptly reported in his book An Eye for an Eye about these Polish extermination camps where thousands of Germans perished. Anyone speaking German in what the new Polish residents considered their new homeland was in danger of being robbed, raped, murdered or thrown into prison. German Jew and Holocaust survivor Josef G. Burg has reported what he experienced in Silesia’s devasted capital Breslau in early 1946 when passing through on his way to a displaced-persons’ camp near Munich (Burg 2018, pp. 81f.):

“The city was horribly destroyed. […] Hate was now not only preached but also practiced. The nights were eerie. Again and again, we heard shooting and people screaming for help. Thefts, robberies and murders were the order of the day. Most of the time, when people inquired, they were told: It was only a German who was shot! And nobody cared. […]

I went for a walk with my family and some acquaintances in the ruined alleys of the city. It was January 1946, and of course we were talking in Yiddish. Suddenly some half-naked children rushed out of a hole in the ground and ran across the wet snow towards us. Crying, they asked us for something to eat.

In the first moment I had recoiled. But then I understood immediately, because the children spoke German. The war had spared them, and like animals they had hidden in caves, where they now led an indescribable life. They thought our Yiddish was German. They thought they were Germans.

But before I could react, one of my companions gave one of the children a brutal kick, so that the girl – who might have been six years old – fell to the ground. My wife, who essentially did not share my views, intervened […]. While my wife busied herself with the children, I went to the nearest bakery store and bought a bag full of rolls to take to the half-starved kids.”

Post-war Poland was in a fever pitch to ethnically cleanse its own territory and also the newly conquered eastern German territories of millions of ethnic Germans. The pogroms that had started at the outset of the Second World War became a steady feature of the daily lives of Germans living under Polish rule for the first several years. Whoever was German and stayed, had only himself to blame. Those who could speak Polish, could blend in. Those who couldn’t or insisted on speaking German had it coming. Although speaking German in post-war Poland was never officially banned as far as I know, speaking German sure led to severe reactions among the new Polish masters. They went to great lengths to wipe out anything that reminded them of the centuries-old German history of the newly conquered territories. Monuments were destroyed; gravestones removed or their German inscriptions chiseled off; archives and all kinds of records in courts, municipal and regional administration centers, churches, media outlets, companies etc. were either locked away in basements or simply thrown away or burned. All this happened under the mendacious slogan that these old Polish territories had finally been recovered after centuries of German oppression…

In other words, like almost all the nations victorious over Germany, Poland was caught up in a post-war anti-German genocidal frenzy. Any claim of German atrocities fueled that fire and was welcomed by the new system that was looking for any excuse to blame the Germans for just about anything, so that they had a “justification” for their policy of ethnic cleansing. At the end of the day, however, the new Polish masters were well aware of the heinous crimes they were committing. Never before in recorded history had such a robbery of territories in conjunction with such a massive ethnic cleansing happened on such a scale and scope. How could any straight-thinking person ever think they could get away with it?

While it is true that Germany’s occupation of Poland during the war created victims and caused quite a lot of damage, this does not justify turning Germans into victims after the war. Two wrongs don’t make a right.

The West-German governments of the first two decades after the war certainly saw it that way, and they insisted that Poland should not get away with this robbery. In fact, except for the communist party, all of West Germany’s political parties, from the socialist SPD to the conservative CDU, insisted during the first several national West-German election campaigns that those robbed German territories must be recovered. At least that is what they told their voters. During those years, a good 15% of them were expellees from East Germany and Eastern Europe. But considering that the world was locked in a Cold War with both sides armed to the teeth with nuclear weapons, with Germany emasculated and divided right in the middle of this worldwide confrontation, there was never a realistic chance of anything being given back to any part of Germany.[1] But hindsight is always 20/20. Back then, people simply could not (or did not want to) imagine that such a huge injustice could ever be accepted.

The Poles, as extremely nationalistic as they were back then, certainly could not imagine that the Germans would ever accept this kind of treatment. No Pole would ever consent to such a treatment of their nation, so why would a German?

The Germans eventually consented, and here is how this came about:

In the toxic, violently anti-German climate in Poland of the immediate post-war period, the new Polish-Stalinist regime held trials against many Germans who were accused of all kinds of wartime atrocities. Given all the circumstances, these trials could not be anything else but Stalinist show trials. Guilty verdicts were pretty much inevitable, no matter the charges. The West-German judiciary was well aware of the unreliable nature of these Stalinist courts’ findings, so no West-German court or prosecutor’s office initially asked for help by any communist country’s institutions for West-German criminal investigations against Germans accused of having committed atrocities during the National-Socialist era. That changed, however, during 1958, when the International Auschwitz Committee lobbied to open criminal investigations against Wilhelm Boger, a former employee at the Political Department of the Auschwitz Concentration Camp. The International Auschwitz Committee was a Polish-communist propaganda organization established in 1952 with its headquarters in Krakow, but because back then not many in the West took anything coming from a Polish-communist organization seriously, they established a General Secretariat in Vienna in neutral Austria. (Tellingly, its headquarters are now in Berlin.) From Vienna, the communist and Auschwitz survivor Hermann Langbein spearheaded a campaign launched in 1958 to initiate a major trial in West Germany against former members of the Auschwitz Camp’s SS garrison (see Rudolf 2003). It is safe to say that Langbein was coordinating these attempts closely with his puppet masters in Krakow and Warsaw.

Once the investigations against Wilhelm Boger were officially opened in August 1958 – and soon were expanded to include many more defendants – the Poles set out to prepare a series of documents of grave importance: Danuta Czech at the Polish Auschwitz Museum used the records available to her to write a day-by-day account of what the Polish-communist authorities wanted the world to believe happened in the Auschwitz Camp during the war. She was to create a streamlined account supporting the findings already “established” by the show trials at war’s end, foremost the Krakow Trial against former Camp Commandant Rudolf Höss, and the Warsaw Trial against other members of the Auschwitz camp garrison. This streamlined account was published both in Polish and right away also in a German translation. To do this, the Auschwitz Museum actually created its own German-language periodical called Hefte von Auschwitz (see Czech 1959-1962, 1964a&b). While German as a language was factually, if not legally, banned in all areas under Polish influence, and while speaking German in Poland in the immediate post-war period could spell doom and disaster for the offender, in the midst of all this anti-German frenzy we find the Polish government in conjunction with one of its museums issuing a German-language periodical. How can we explain that?

The smoking gun clearly points to this project aiming at decisively influencing the expected upcoming Auschwitz Trial soon to be held in West Germany. And indeed, if we read the records of the Frankfurt Auschwitz Trial, references to Czech’s Hefte von Auschwitz can be found there, and they even served as evidence; in fact, Danuta Czech herself appeared as an expert witness during that trial. But more importantly, it can be assumed that the record Czech created was used to “instruct” Polish witnesses before traveling west to testify in Frankfurt, making sure that they all delivered a coherent story in line with what the Auschwitz Museum’s officials had ordained to be “the truth.” That this massive manipulation of Polish witnesses happened, indeed, was revealed during the trial itself, as I have reported elsewhere (Rudolf 2019, pp. 110).

The strategy behind this was to force the Stalinist propaganda version of what happened at Auschwitz (and also elsewhere during other, later trials) down the West-German judiciary’s throat, establishing it as the only acceptable narrative. Making the West-German judiciary confirm the veracity of the enormous claims made by Polish historians (with the support or even at the behest of many Jewish historians, to be sure) would put a gigantic Mark of Cain onto Germany, an admission of guilt of such preposterous enormity that anything which happened to Germany and the German population at war’s end and thereafter could only be seen as a well-deserved punishment for unfathomable crimes. It was the continuation of the war by the means of psychological warfare. It was what the Germans call “Raubsicherungspolitik” – literally Robbery-Securing Policy, a policy designed to secure the spoils of history’s greatest robbery ever, the annexation of East Germany by Poland, and the ethnic cleansing of its German population.

It worked. The Frankfurt Auschwitz Trial proved to be a watershed event in German history. After it, a deluge of similar trials followed, continuing to this very day against 100-year-old geriatrics, all following the same script of the Stalinist show trials of the immediate post-war period. It turned a once-proud German nation into a nation of self-flagellating spineless creatures who agree that all that was done to them during and after the war – carpet bombing, mass murder of “disarmed enemy forces,” mass deportations to Siberia, ethnic cleansing, starvation policies, dismantling of Germany’s industrial equipment, robbery of its patents – was a just punishment for all the crimes allegedly committed during the war. In fact, some self-hating Germans insist that the only atonement befitting the German nation’s crime of “the Holocaust” is for them to disappear forever from the face of the earth: “Germany, you have done enough for mankind; now disappear!” In the face of Hitler’s (alleged) crimes, implementing any policy aiming at the preservation of the indigenous German population and culture is generally considered utterly unthinkable. Today’s demographic collapse of the indigenous German population, which will cease to exist in just a few generations more, is a logical consequence of this.

If there were tens of millions of a Polish surplus population, they could now take over the rest of Germany, and Poland could celebrate its ultimate victory over its western neighbor! The only problem with that is that there is no Polish surplus population. In fact, with spreading their Stalinist wartime propaganda, the Poles poisoned the well for all European populations the world over, their own included. None of them has any ability to implement any policy of cultural and ethnic self-preservation, for whoever wants to follow such a policy, is called a Nazi by his opponents, and that’s the end of that… Hence, Poland’s indigenous population is undergoing the same demographic collapse as Germany’s; and Italy’s; and Greece’s; and Spain’s; and, and, and…

In the age of the Pill, population and civilization collapse is the true big challenge of Europe (and soon other areas of the world as well). While Europe is paralyzed by the aftereffects of wartime propaganda, millions of immigrants mainly from Africa and the Middle East are slowly but surely taking over the entire continent. Within a century or so, the rest of the currently indigenous European population will be pretty much completely replaced with the new immigrants, with some of the old inhabitants interbreeding with the newcomers, just like it happened to the Neandertals. Europe’s history repeats itself, only this time, unlike in previous prehistoric instances, we know the reasons for this population exchange.

Danuta Czech’s mis-chronicling of Auschwitz is one of the main reasons why indigenous Europeans are currently defenseless against the collapse of their populations, and thus of their culture and maybe even their civilization.

They all are Danuta Czech’s victims. Thank you, Danuta!

In the present book, Carlo Mattogno proves beyond the shadow of a doubt that Danuta Czech’s Auschwitz Chronicle is exactly what is to be expected when knowing its role in history: An account filled with many correct statements about a camp that was an injustice from its very beginning, but infused with a large amount of propaganda lies created to serve the political agenda described here.

Germar Rudolf, 29 December 2021

[1] As a matter of fact, in the mid-1980s, when the Soviet Union faced bankruptcy, Mikhail Gorbachev offered to sell the northern part of East Prussia, which had come “under Soviet administration” after the war, for a billion deutschmarks to West Germany, but Bonn turned down that offer. Considering that this enclave now sits like a festering Russian thorn in the midst of NATO and EU territory, I guess Berlin thinks differently about this today, but it is unlikely that Russia will ever repeat that offer…